Chess, Warhammer, Battlestar Galactica.

NB. While there are always caveats to strategy depending on the game state, moves your opponents are making, and what army you are playing, these general chess principles can help advise strategy and thought processes during a game of Warhammer.

When you find a good move…

In my previous post, found here (Improve your Warhammer: Chess edition), I discussed that thinking during a game of Chess, or Warhammer can be divided into fuzzy and precise thinking. Fuzzy thought being the fumbling process of getting acquainted with the potential of a position by trying out likely looking possibilities; precise thought is the calculation of essential variations, or in Warhammer terms, the likelihood of your dice not betraying you.

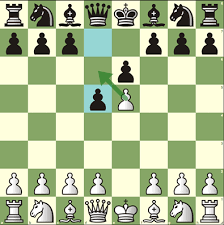

But when you’ve fumbled and analysed, and all the signposts point to one particular move – whether this being finally pushing out an aggressive attack, or deepstrike – when is the moment to sign contracts and play it? The great German player Dr Siegbert Tarrasch advised: ‘When you’ve found a good move, look for a better one.’ What nonsense! When you’ve found a good move, play it! Good moves are few and far between. Don’t talk yourself out of them. But make sure they are as good as you think.

There is a very useful rule for deciding on a restaurant in Paris: wander the streets until you find one restaurant you like; then go to the first one you see that is better. But it only works in Paris, or another city where there are many good restaurants. When looking for a good move in a chess position, or in a Warhammer game, it’s like searching for a restaurant in some run-down holiday resort in England. Hence the practical rule for good moves.

When you’ve found a good move, savour it!

Strong players always think a goods deal before playing ‘obvious’ winning moves. If it’s really a winning move, you can even spare the time to look at every legal reply your opponent has at his disposal. And having tied up every loophole, you paly the move with calmness and confidence.

Sometimes in Warhammer, ‘good moves’ become apparent very quickly, when a hole is left for a deepstrike, when your opponent moves a unit just a little bit too close, when you draw the perfect secondaries and now it’s time to pull the trigger, or when you setup the ultimate overwatch/reactive move bait. When this does occur, instead of jumping the gun, consider at least one more option and see if it changes your mind.

Hierarchies of thought

Expanding on our ideas of fuzzy and precise thought, we must consider another way of thinking that is the key to understanding not only good chess, but good Warhammer.

The best way to explain it is by considering our thoughts to be arranged in a hierarchical structure. At level zero, we have precise calculation. Has the opponent’s last move (or turn in Warhammer) left him open to a killer punch? If not, does it threaten anything that demands immediate action? At level two, we browse the static features of the position – the pawn formation, the weak squares, the safety of the kings, the potential endgame advantages and other such elements that lead to the formation of a general strategy – or in Warhammer, the board state, the open spaces, the safety of primary, the potential secondaries that can be drawn, the impact of going first or second and end of turn scoring, the path to victory you form at the start of the game and how it changes throughout. However, the real hard work goes on at the intermediate level one, where tactics and strategy play equal roles. Here is roughly how it works.

You start at level zero, sorting out the immediate tactics of the position. If that reveals no clearly best move, you move up to level two, where some fuzzy thought suggests moves that may help with strategic objectives. Those moves are sent to level zero for a tactical health check and any passed fit move to level one to be looked at in more detail. For it is here that we assess the strategic gains that may be made by tactical means. And when those are established, they must be referred back to level two, because such discoveries may lead to a modification of our entire strategy.

This constant interplay between strategy and tactics is an essential,. if sometimes confusing, part of good thinking. Like a novelist’s two modes of creating (when ideas are left to flow) and editing (when precise words and expressions are chosen), vague strategic planning (creative) and precise tactics (editing) require different levels of concentration. Here’s a practical tip:

Think strategies when it’s your opponent’s turn; sort out the tactics while your own clock is running.

This is invaluable as clocks become ever present at Warhammer tournaments. You can and should be using all the time available to you in a game of Warhammer to maximise your chances of winning, and by structuring your thought in this way you can use the time you have most effectively, when you have it.

I go here, here goes there…

William Hartston outlines that one of the best excuses he ever heard was from a man who had just lose to female opponent. ‘She completely disrupted my thought processes,’ he complained. ‘Every time I tried to calculate something, I’d begin: “I go here, he goes there,’” and then I’d have to correct myself: “No it’s I go here, she goes there”.’

Apart from the ready-made excuse in such circumstances, the ‘I go here, he goes there’ method is a good habit to get into – for it is surprisingly easy to forget that little rule about White and Black making alternative moves (or that your opponent has the opportunity to react to your plans on their turn). There are two circumstances where such a fault often occurs.

- When both sides have clear plans that appear to have no point of interaction, trying to analyse them properly can seem like trying to sing two different songs at the same time, alternating the notes of one with those of the other.

- When you have followed a forcing variation for several moves, but can’t quite see what your opponent’s next move is likely to be.

Sometimes, when you can’t find a move for your opponent, it’s because he hasn’t got one.

Is it surprisingly easy to reject a very strong move because you cannot see how your opponent defends against it. When your opponent has only one defence to your threats, you will certainly continue your analysis, but when he has no defence at all, there is the temptation to reject the whole ling and look at something different simply because you cannot see how to continue the analysis. ‘I go here, he goes nowhere at all’ may be the real signpost to victory.

Applied to Warhammer, this can be construed to Zugzwang. A concept in chess where one player is put at a disadvantage because of their obligation to make a move. In chess, it may be easier to not find a move for your opponent to construct a defense than in Warhammer, but in Warhammer if you can manoeuvre yourself into a position during a game where your opponent simply has no good moves, and you can maintain that position, you win.

I hope you took something away from this post and can understand how general chess principles and strategies can be applied to situations in Warhammer games. If you have anything you would like me to write about comment below!

Cya nerds.

If you are interested, the lessons and strategies discussed in this article are taken from the book:

Improve your chess by William Hartston

Leave a comment